The People

Those who lived at Poverty Point more than 3,000 years ago left no written records of their day-to-day lives. We know that the site was a ceremonial center that was once home to hundreds or perhaps thousands of people, as well as a trading hub unmatched by any in North America at that time.

Archaeologists have learned about these people by the materials they left behind—artifacts and archaeological features—as well as what they didn’t leave behind, such as burials and crop remains.

Burial mounds were common throughout the southeastern and central U.S., yet the absence of human remains at Poverty Point suggests these monumental earthworks, built by hand, were being used for other purposes.

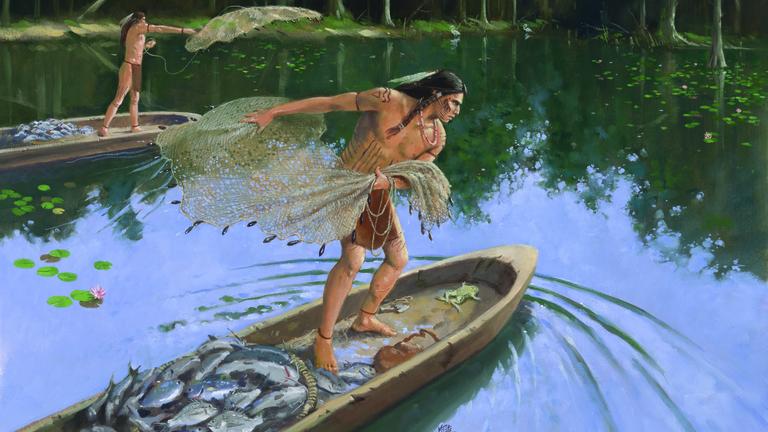

Just as curious is the lack of domesticated plant remains found at Poverty Point. Archaeologists have found evidence of nuts, persimmons and grapes, which—along with fish, deer and other wild foods—were more than sufficient for survival. This makes sense, as the Lower Mississippi Valley is one of North America’s most fertile regions, abundant with food that was literally ripe for the picking. Foraging was a fundamental part of Poverty Point society.

So was commerce. The site was once at the center of a huge trade network. Seventy-eight tons of rocks and minerals from up to 800 miles away were brought to Poverty Point, an area built on an elevated landform, Macon Ridge, that contained no stone of its own. Its people needed this raw material to craft into weapons, tools and ceremonial items. This would have been impossible without help from faraway travelers, or locals traveling by boat to collect rocks themselves.

We know much about Poverty Point society just by where they built their homes. Looking over Bayou Macon, it’s easy to assume that these men and women relied on the river. Thanks to animal and plant remains, we know their diet consisted largely of fish, alligators, frogs, turtles, deer, hickory nuts, aquatic tubers, fruits and other wild foods. Most of the animal bones found on-site were from locally caught fish.

The question of why Poverty Point was abandoned remains unanswered. A subsequent American Indian group came along around 700 A.D. and reused a small part of the site, but otherwise, it remained abandoned until its rediscovery in the 1800s.